By Farrokh Rahimi, Sasan Mokhtari, and Ali Ipakchi

This article was originally published by IEEE Energy Sustainability Magazine.

Sustainability in electric power systems entails measures to ensure a reliable and resilient supply of electricity, promoting social and economic benefits, while minimizing negative environmental impacts. Reliability requires measures to ensure continuity of supply in the face of credible contingencies, such as grid equipment or generation unplanned/forced outages. Resilience entails measures to enable the grid to resist, react, and recover in case of rare but high impact natural or malicious contingencies, such as hurricanes and cyberattacks. Social benefits involve measures to enable prosumers (consumers with active demand-side assets, such as distributed generation, storage, or both) to maximize the return on their demand-side asset investments, lower energy costs for passive consumers, and provide environmental benefits for society at large.

Introduction

The transition toward sustainable energy systems in the face of climate change concerns, greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation objectives, and pollution reduction targets involves a large penetration of renewable sources of energy at both the bulk level and the grid edge. Driven by sustainability regulation on the one hand and increasing expectations for customer choice on the other, the electricity grid is on a 3D pathway of Decarbonization, Decentralization, and Democratization. Energy sustainability in the emerging grid hinges on proper coordination among agents with different objectives and incentives along this pathway.

The current grid planning and operating practices and procedures are not conducive to energy sustainability in the face of climate change concerns, GHG mitigation objectives, and pollution reduction targets. As a case in point, while energy transition and grid transformation are driven by high levels of environmentally friendly variable energy resources (VERs) at the bulk level and distributed energy resources (DERs) at the grid edge, the present operating procedures result in frequent curtailment of these resources because of their variability in the face of current conservative limits on injections into and withdrawals from the grid. Moreover, in the emerging high VER/DER grid, a lack of adequate coordination among the various actors, who separately pursue their economic incentives and operational objectives, exacerbates the problem for both the grid operators and grid users.

In this article we take a two-pronged approach to address these issues, with dynamic instead of static operating limits and the use of incentive-based collaborative operational coordination. To quantify the sustainability impact of these innovative measures, we define some sustainability metrics. We then elaborate on the first measure, namely a new process to establish dynamic operating envelopes (DOEs) at various grid locations, allowing for dynamic rather than conservative static and limits on injections and withdrawals at various cross sections of the grid. Then we address the second measure, i.e., the important issue of operational coordination among DER asset owners/operators, aggregators, distribution system operators (DSOs), and bulk power grid and market operators to maximize sustainability metrics. We conclude by providing results of pilot projects and field implementations of operational coordination platforms and operating strategies involving these innovative sustainability enhancement techniques.

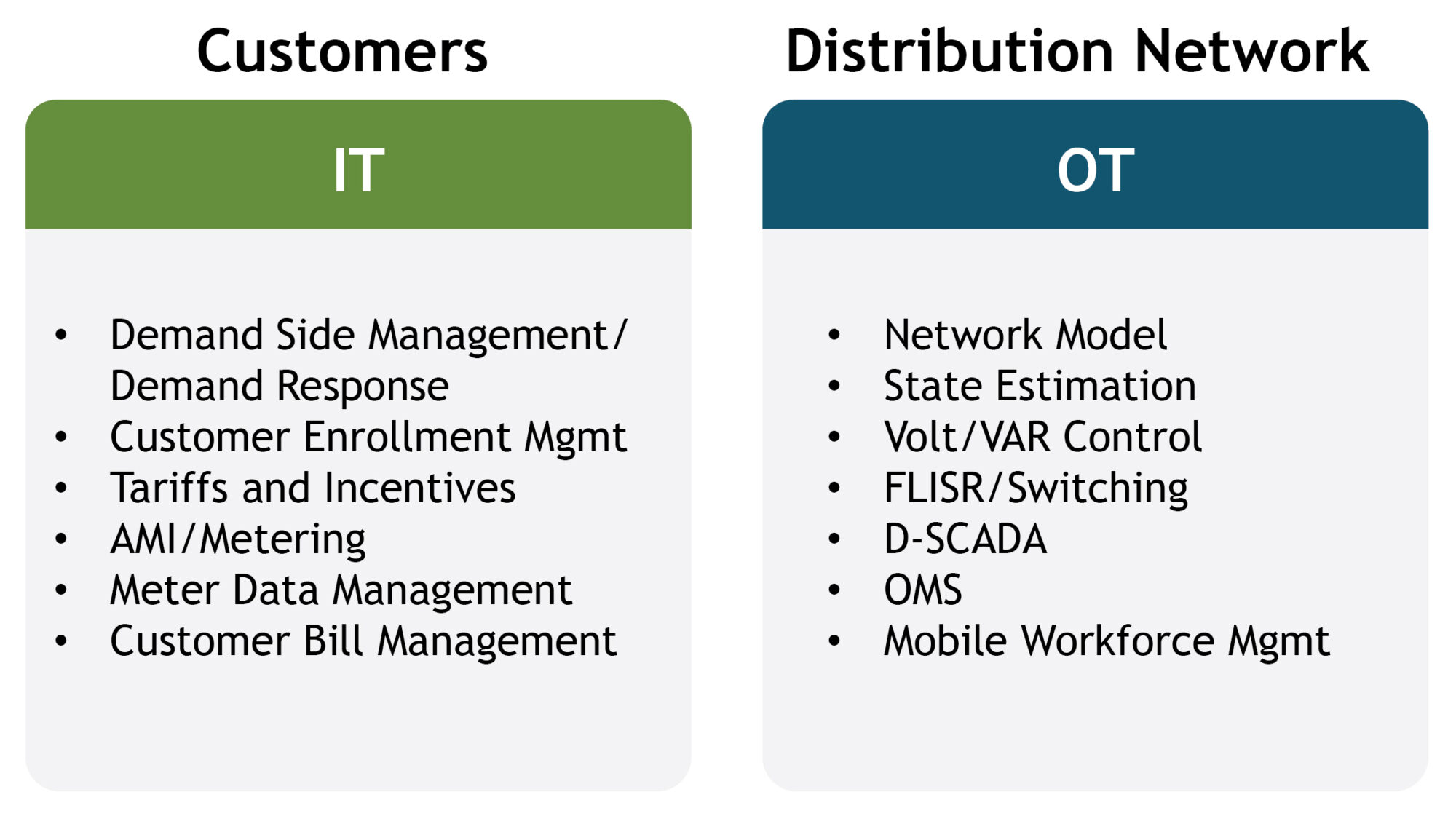

Figure 1 shows the conventional distribution utility operations leveraging IT for interactions with consumers and operations technology (OT) for grid operations.

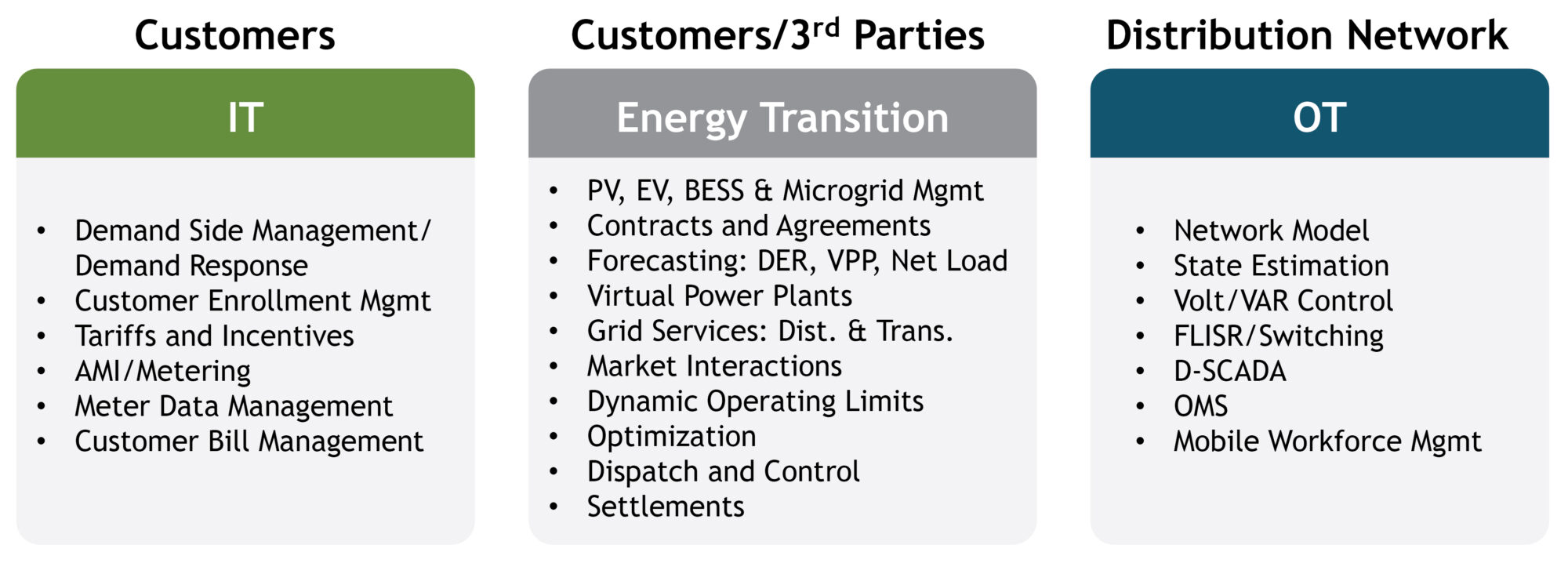

As illustrated in Figure 2, under an energy transition to a sustainable grid, with the emergence of active consumer assets at the grid edge, utility control room operation must account for both the impact of the DERs on the grid as well as potential cost-effective opportunities that demand-side flexibilities provide for the provision of grid services.

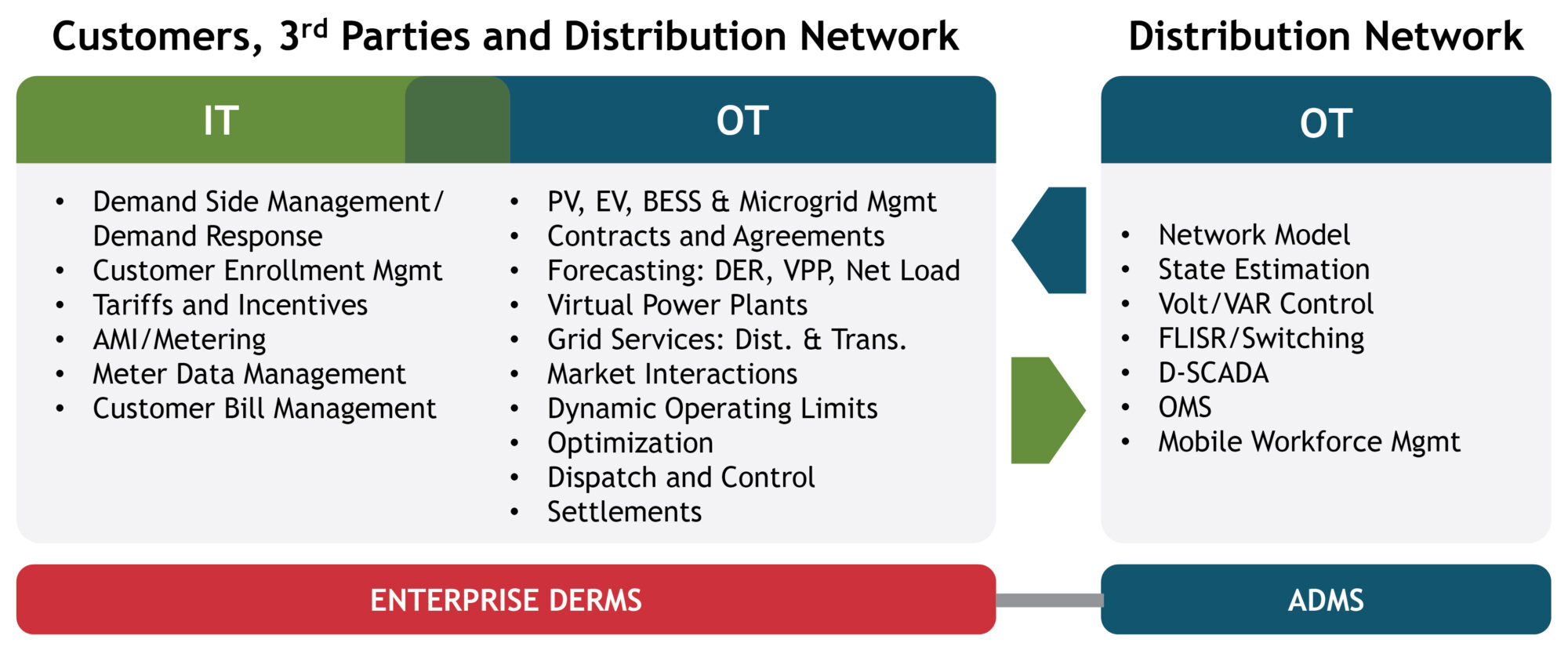

Conventional control room distribution management systems (DMSs) deal primarily with the control and monitoring of utility-owned field assets, such as breakers, reclosers, transformer taps, capacitors, reactors, etc. As illustrated in Figure 3, the emerging distributed energy resource management systems (DERMSs) help extend the reach of a conventional DMS to grid-edge assets through information exchanges and application programming interfaces (APIs).

While DERMS provide a venue to preserve and potentially enhance utility operations in the emerging sustainable energy transition paradigm, a lack of adequate coordination among various actors, who are separately pursuing their economic incentives and operational objectives in the emerging high VER/DER grid exacerbates the grid operations problem.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The section Energy Sustainability Metrics defines some metrics to quantify sustainability. The section Dynamic Operating Limits presents a new process to establish DOEs that allows for dynamic, rather than conservative static, limits on injections and withdrawals at various cross sections of the grid. The section Operational Coordination addresses the important issue of operational coordination among DER asset operators, aggregators, DSOs, and bulk power grid and market operators to maximize sustainability metrics. The section Implementation and Illustrative Examples presents a sustainability-enhancing operational coordination platform along with some use cases and illustrative examples. This section includes results of pilot projects and field implementations of the operating strategies relying on the innovative techniques presented in the sections Dynamic Operating Limits and Operational Coordination in view of the sustainability metrics presented in the section Energy Sustainability Metrics. Conclusions, closing remarks, and plans for further research and development are presented in the section Concluding Remarks.

“Dynamic hosting capacities open the way to accommodate larger volumes of renewable resource interconnections without the need for costly grid upgrades.”

Energy Sustainability Metrics

Energy sustainability can be assessed across three main axes.

- Supply sustainability: Ensuring the continuity of electricity supply, vis vis renewable supply fluctuations and grid contingencies (outages or derates).

- Environmental sustainability: Reducing air pollution, GHG emissions, water usage, and other negative environmental impacts associated with electricity generation.

- Economic sustainability: Ensuring that electric power systems remain financially feasible and provide affordable energy for all consumers.

Metrics to help assess energy sustainability involve evaluating service quality, resource use, environmental impact, and social and economic factors in addition to conventional reliability and resilience metrics. The following are some key sustainability metrics:

- reduction of renewable curtailment

- increase in interconnection of clean energy production and consumption resources

- economic efficiency (reduction of energy usage per unit output)

- renewable portfolio share, i.e., the percentage of total energy consumption from renewable resources (solar, wind, hydro, and biomass)

- affordability (lower energy rates for consumers)

- energy carbon intensity (CO2 emissions per unit of energy generated)

- GHG intensity (GHG per unit of energy generated)

- consumption carbon reduction (reduction of emissions due to electrification of heating, transportation, etc.)

- energy return on investment (ratio of the energy produced to the energy invested in its production).

These metrics may be used to measure the impact of the innovative technique proposed here: DOEs and collaborative operational coordination.

Dynamic Operating Limits

Conventional electricity grid operation is based on maintaining flow limits and voltages within pre-established limits. These limits are often determined conservatively based on static grid conditions, which constrain the maximum utilization of renewable resources because of their variability. Prominent examples are the need for costly investments in grid upgrades to accommodate new renewable resources and the curtailment of renewable generation when exceeding the conservative operating limits.

In the context of energy sustainability, two types of dynamic operating limits may be distinguished based on a combination of temporal and geographical dominations.

- In the planning time frame, they take the form of a dynamic hosting capacity instead of the current practice of using a conservative static hosting capacity limit. Dynamic hosting capacities open the way to accommodate larger volumes of renewable resource interconnections without the need for costly grid upgrades. The concept of dynamic interconnection is gaining popularity; it allows renewable energy-producing and energy-consuming resources to interconnect to the grid with agreements to occasionally adjust their energy injections and withdrawals to avoid violating grid constraints. This results in higher amounts and volumes of carbon-free energy-producing resources (such as solar and wind) as well as higher amounts and volumes of clean energy-consuming resources [such as electric vehicles (EVs) and EV charging stations] to connect to the grid.

- In the operational time frame, they take the form of DOEs with temporal profiles at various grid cross sections. The DOE time resolution may be established in hourly or subhourly temporal granularity. This enables the reduction of curtailments of variable clean energy resources as well as clean energy-consuming resources in the operational and dispatch time frames.

By integrating more renewable energy into the grid and reducing the reliance on fossil fuels, DOEs support the transition to a low-carbon energy system.

In this article we concentrate mainly on DOEs as they directly impact the proposed companion measure of operational coordination mechanism.

DOEs define the maximum allowable exporter import capacity for individual network locations (service points, feeders, and substations) as well as allowable injections and withdrawals of DERs at any given time. These limits are dynamically calculated based on near real-time data, including the following:

- network real and reactive power capacities

- electricity demand and consumption patterns

- weather conditions and associated renewable generation forecasts

- market price signals.

DOEs can be leveraged as localized/decentralized grid management tools to ensure that DERs can contribute optimally to grid reliability, resilience, and economics without causing overloads or voltage violations. Adopting DOEs instead of static operating limits enhances energy sustainability, which may be quantified using the sustainability metrics defined in the section Energy Sustainability Metrics.

- By enabling DERs to export or import energy within dynamic limits, DOEs reduce the curtailment of renewable generation and increase the efficiency of energy distribution.

- Real-time adaptability to changing conditions enhances the grids ability to manage fluctuations caused by renewable generation variability or sudden changes in demand.

- DOEs provide greater visibility and control to DER owners, enabling them to maximize their participation in energy markets and improve their return on investment.

- By integrating more renewable energy into the grid and reducing the reliance on fossil fuels, DOEs support the transition to a low-carbon energy system.

To effectively develop and use DOEs, several challenges must be overcome, including but not limited to the following:

- Data and communication infrastructure: The real-time nature of DOEs requires advanced data acquisition and communication systems. Reliable, secure data sharing among grid operators, DER owners/operators, aggregators, and other stakeholders is essential for establishing and using DOEs.

- Computational complexity: The calculation of DOEs requires three-phase distribution optimal power flow algorithms and predictive analytics, which may demand significant computational resources.

- Regulatory and market integration: Implementing DOEs necessitates regulatory frameworks that enable dynamic pricing, flexible tariffs, and appropriate incentives for DER owners. Market mechanisms must be designed to accommodate variable operating limits.

- Equity concerns: Ensuring fair access to network capacity across different regions and user groups is a potential concern. Strategies must be developed to avoid disadvantaging smaller DER owners or remote communities.

- Advanced forecasting tools: The integration of weather forecast models, demand forecasting, and machine learning algorithms is needed to improve the accuracy of dynamic limit calculations.

In short, DOEs are a transformative solution for the enhancement of energy sustainability in the emerging electricity grids, addressing the challenges of integrating renewable energy and DERs while improving grid efficiency and resilience. By leveraging real-time data and advanced analytics, DOEs optimize resource utilization and empower stakeholders in the energy transition toward enhanced sustainability.

Operational Coordination

Under the energy sustainability paradigm, the rapid growth of intermittent generation and battery energy storage at the bulk power grid and the growing penetration of DERs, including front-of-the-meter and behind-the-meter (BTM) generation and storage at the distribution level as well as smart devices, are significantly impacting the current grid supply. This demands balancing practices that are driven primarily by conforming load forecasting and the scheduling and dispatch of conventional generation resources that use stable fuel sources (fossil fuels, nuclear, and hydro).

Additionally, the growing forecast inaccuracies due to the lack of visibility and availability of supporting data and models at the distribution level result in energy market inefficiencies, excessive generation and transmission reserve needs, and reliability challenges, including grid congestion and a shortfall of adequate resource flexibility for ramping and energy balancing. These issues are further exacerbated by the increased frequency and severity of extreme weather conditions, with a significant negative impact on intermittent renewable energy resources, where more accurate look-ahead situational awareness and a corresponding supply sufficiency become critical to mitigate threats to reliable and resilient sustainable grid operations.

The existing grid operating procedures and practices must be modified and augmented with additional data and modeling techniques and improved tools to provide enhanced forecasting accuracy and situational awareness. This is needed to maintain the established reliability, resiliency, and efficiency standards through better management of uncertainties resulting from the proliferation of renewable and distributed resources at the emerging grid transmission and distribution (T&D) levels under an energy sustainability paradigm.

The rise of demand-side flexibility, through the rapid growth of remotely controllable devices, like smart thermostats and other DERs, is a game changer for sustainable electricity grid operations. These mostly BTM customer- or third-party-owned resources can reduce demand or inject power at the edge of the distribution grid. By incentivizing consumers to adjust, or allow the utility to control, their energy use based on grid conditions, utilities can leverage BTM DERs to maintain a power balance (both real and reactive)without needing expensive new infrastructure. The kilowatt-level DERs can be aggregated into megawatt-level virtual power plants (VPPs)via a well-designed enterprise DERMS platform.This aggregation transforms each judiciously selected group of smaller resources into a single, collective, controllable power source, capable of not only providing grid services but also enhancing resource adequacy and augmenting grid resilience.

In the move to energy sustainability, to maintain electric power supply reliability, resilience, and affordability while promoting clean environmental objectives, the following two operational improvements are essential:

- enhanced look-ahead situational awareness, leveraging advancements in information processing, data exchange, data analytics, and data and systems integration while considering prevailing business practices, the changing stakeholder landscape, and regulatory considerations

- enhanced operational coordination among different actors, each with their own operational objectives.

In achieving these objectives, several operational gaps must be filled.

- addressing shortcomings of the current top-down distribution factor-based load forecasting allocations. This will be primarily addressed with the bottom-up forecasting element of the project

- providing the grid operators with the required data, including data aggregated at the seams between T&D

- proper modeling of DER resources and DER aggregations (VPPs) on T&D levels

- supporting participation of microgrid resources in the energy markets during normal conditions and utilizing the resources to enhance system resilience under severe conditions

- elaborating DER registry and associated data exchanges among stakeholders, including the independent system operator(ISO)/regional transmission organization(RTO), DSO, load serving entities(LSEs), community choice aggregations(CCAs), and aggregators.

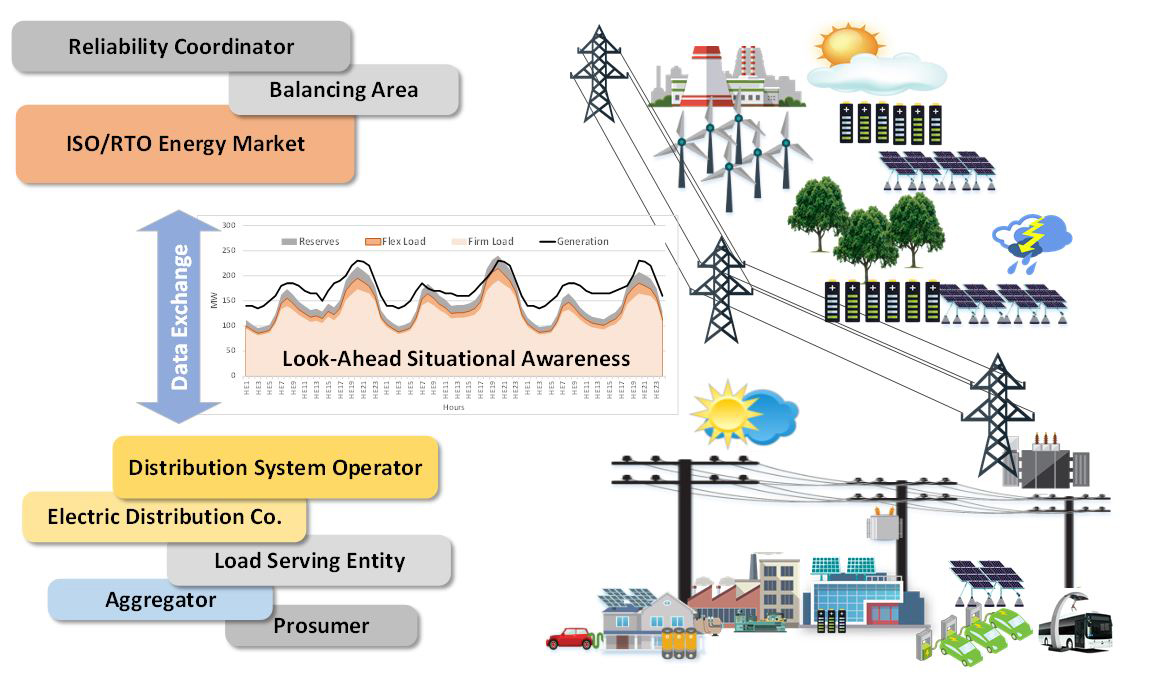

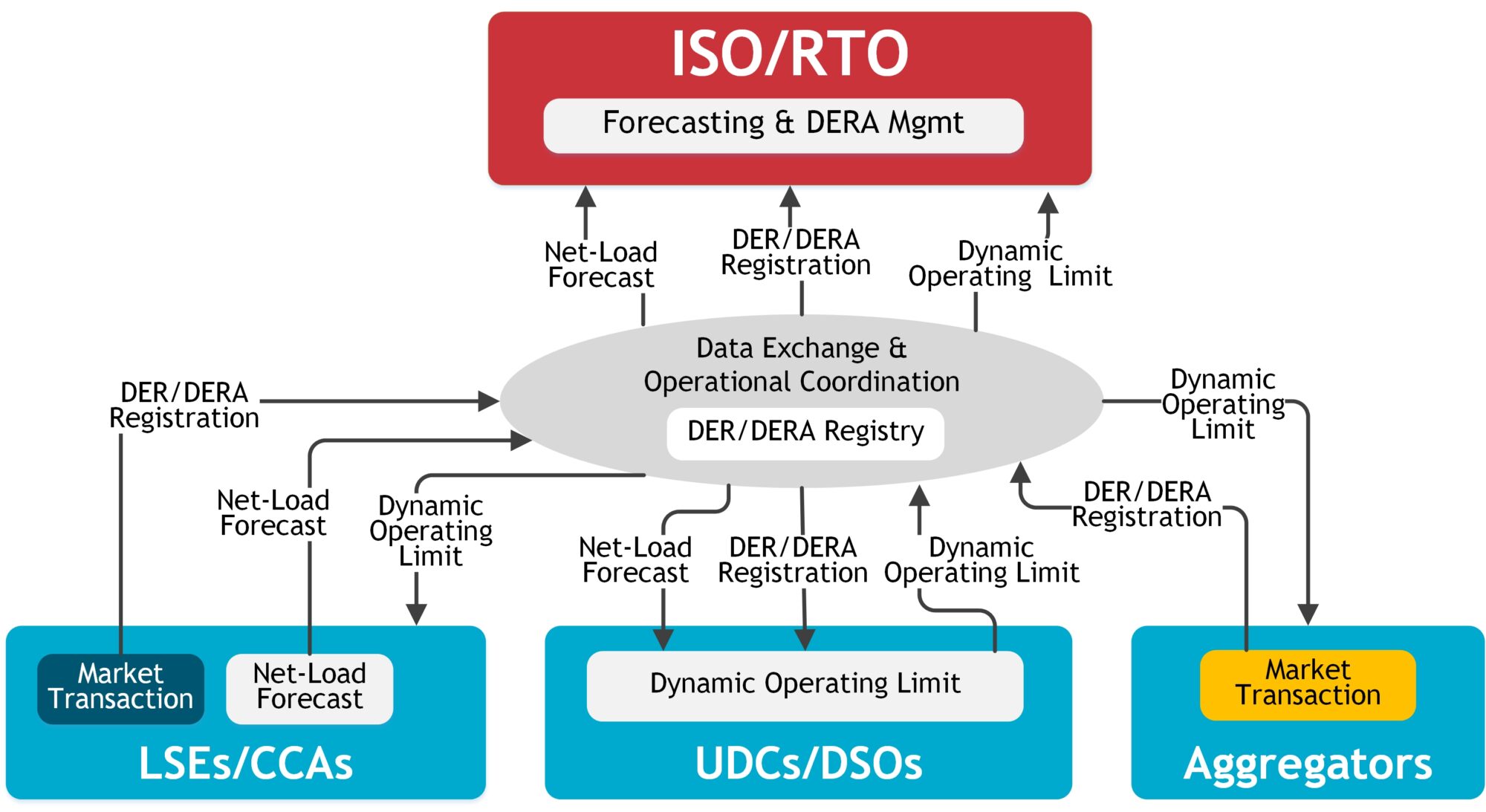

As illustrated in Figure 4, data modeling and data exchange requirements for load, generation, and interchange forecasting in various operational time frames must be addressed considering the following:

- classification and data modeling of transmission-connected battery storage, hybrid resources, and microgrids to support accurate forecast of their operation, including operating state, load, and generation levels

- classification and data modeling of demand-side and DER types to support accurate forecast of their operation, including operating state, demand, and generation; individually and aggregated at pricing nodes, zonal, or at substation levels. This includes but is not limited to

- battery energy storage

- hybrid resources and microgrids, which may include two or more of the following assets: photovoltaic (PV) generation, battery storage, backup generation, and demand response

- EV charging loads, available curtailment, and vehicle-to-grid dispatch capability for different classes of EV charging and vehicle-to-grid capabilities

- data exchange frequencies, updates, accuracy, and data validation requirements

- stakeholder classifications, roles, and responsibilities with respect to data origination, systems of records, and look-ahead data exchanges

- utilization of as-operated distribution grid topology to aggregate grid-edge device capabilities and conditions at the seams between distribution and transmission, including bulk power pricing nodes and supply substations, among others.

Figure 5 provides a straw-man stakeholder model for the required data exchanges with ISO/RTO market operations and reliability coordination functions.

The proposed operational coordination approach is based on the following assumptions:

- Reliable operation of the distribution grid is the responsibility of a DSO, which can be a function of a distribution utility.

- For use at bulk power and ISO/RTO energy market applications, the demand-side resources (generation, storage, dispatch flexibility, gross load, etc., and also bids and offers) are represented at aggregates at the pricing nodes or seams between distribution and transmission. Aggregates may be referred to as DER aggregations (DERAs), or VPPs.

- The aggregator function can be provided by third parties, CCAs, or utilities.

- DER and DERA schedules and operations are subject to DSO feasibility checks, distribution constraints, and approvals to avoid potential distribution grid reliability challenges, such as circuit overloads, reverse flows, voltage violations, and excessive phase imbalances.

- The ISO/RTO can dispatch DERs including demand response and microgrid resources to enhance system resilience under abnormal and extreme conditions.

The development, implementation, and integration of the required technologies, processes, and enhanced functionality are outlined as follows:

- design, development, and deployment of the infrastructure to facilitate, and to an extent practically automate, the data exchange operations across the stakeholders, including aggregators, service providers, microgrid operators, LSEs, DSOs, ISO/RTOs, balancing areas, and reliability coordinators

- DER and DERA registrya regional system of records, including content, and such functions as automated validation of data elements and proposed aggregations based on distribution grid as-operated topology, data access and data update authorizations, etc.

- operational and performance requirements of the data exchange infrastructure and DER registry

- incorporation of enhanced resource modeling, data availability, look-ahead capabilities, and operating practice adjustments with the existing stakeholder (ISO/RTO)systems

- operational process and operating procedures for automated exchange and dissemination of the data across stakeholders in a secure, reliable, and high-performing manner

- DSO functions for operational coordination [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Order 2222], the use of the DER registry, and the utilization of dynamic hosting capacity/DOE for distribution reliability management and data exchange infrastructure.

Implementation and Illustrative Examples

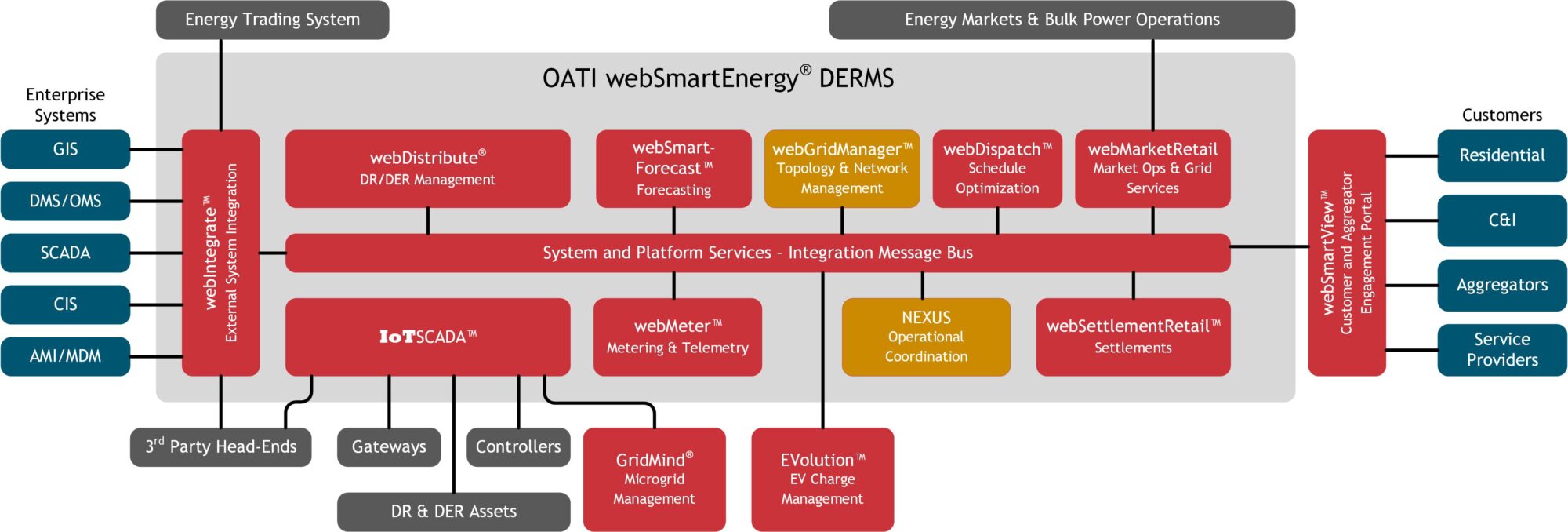

In this section we illustrate the implementation and use of the innovative mechanisms described in the sections Dynamic Operating Limits and Operational Coordinationthe DOEs and collaborative operational coordination. We start by presenting a DERMS platform that includes these two functions along with a number of other functions in support of sustainable energy grid operation. The platform, webSmartEnergy DERMS, has been developed by Open Access Technology International (OATI) and is illustrated in Figure 6.

The platform is designed for use primarily by the distribution utilities, with provisions for interactions with other sustainable energy grid actors, including DER asset owners/microgrid operators, DER aggregators, CCAs, LSEs, transmission system operators, and ISOs/RTOs.

The platform is designed based on a software-as-a-service philosophy using secure web services; the modules are shown with their functions and web-based names. As highlighted in Figure 6, DOEs are computed by the module webGridManager, and operational coordination is accomplished by the module Nexus.

DOEs Module

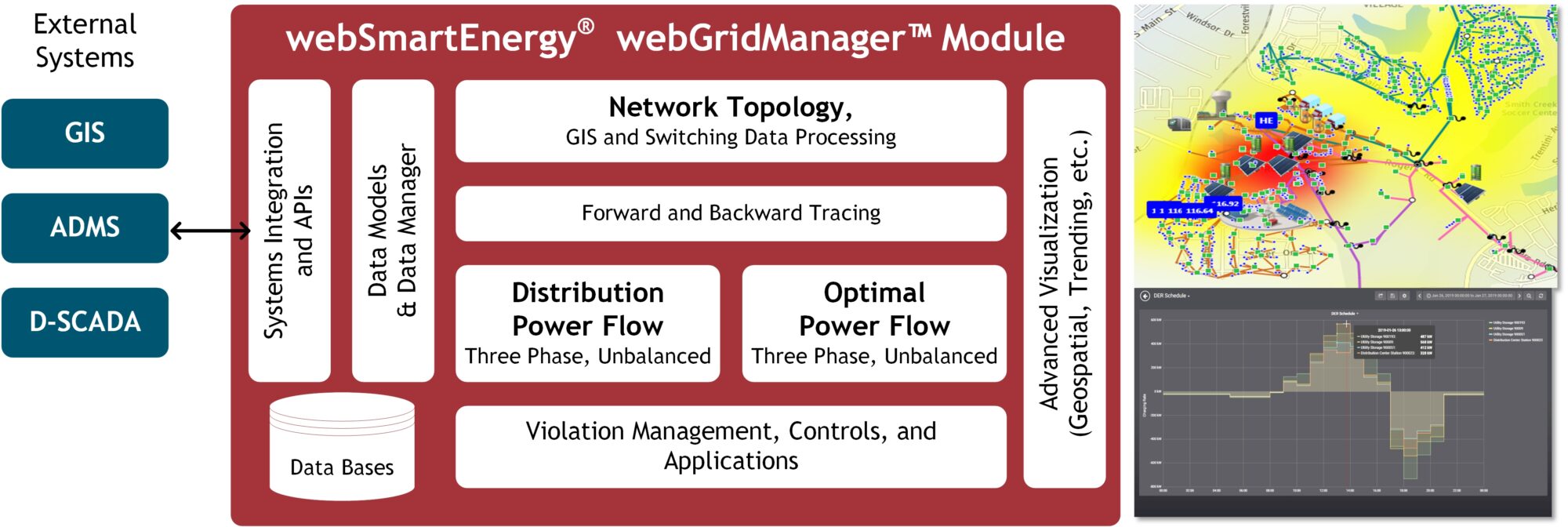

The topology and network management module (webGridManager) is a detailed distribution topology and power flow modeling capability to support the DERMS functionality related to distribution grid loading, voltage management, violation management, optimal power flow, and dynamic hosting capacity/DOE computations. It provides for real-time situational awareness, extending visibility and control from primary distribution facilities and equipment to grid edge devices and assets. It combines a comprehensive modeling of the distribution network and topological connectivity, including providing three-phase ac power flow model analysis including BTM and front-of-the-meter DER assets, required capabilities for real-time and operations planning power flow computations, and violation analysis with preventive and remedial actions and geospatial displays. Figure 7 shows the main submodules comprising webGridManager.

DOEs are established at various grid locations, including the service transformer, feeder, substation, and T&D interface. Rule-based logic is then employed where needed to allocate service-point DOEs to individual DER assets, as illustrated in Figure 8.